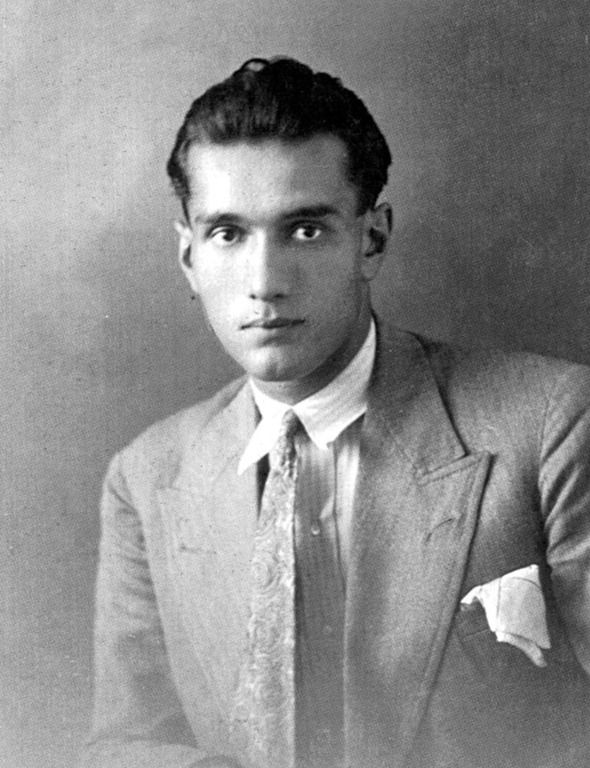

GIUSEPPE TERRAGNI (Meda 1904 – Como 1943)

Member of Gruppo Sette, which since 1926 played a prominent role in the birth and definition of Italian Rationalism, was one of the most important representatives of modern architecture in Italy between the two wars. Among his many works:

“Novocomum” (1927-29)

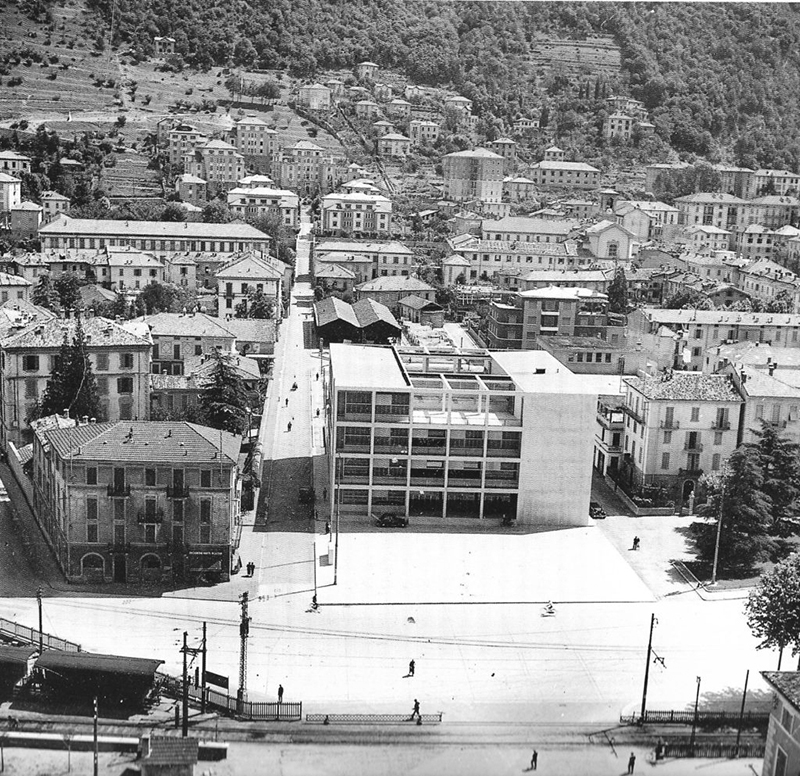

“Casa del Fascio” (1932-36) in Como.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES BY ATTILIO A. TERRAGNI

During his short life, Giuseppe Terragni experienced an intense career spent entirely under Fascism.

Born in Meda in 1904, he will turn eighteen in the year of the march on Rome and Benito Mussolini’s seizure of power (1922), only to die a few days before his overthrow, on 25 July 1943.

All his works are concentrated between Como, his city, and Milan where he graduated from the Polytechnic in 1926 in a rather traditionalist academic climate dominated by such professors as Gaetano Moretti and Piero Portaluppi. Terragni is among the recent graduates or undergraduates who give life to Gruppo 7 posing new questions to the Italian architectural debate rather provincial at that time. It includes Luigi Figini, Gino Pollini, Carlo Enrico Rava, Sebastiano Larco, Guido Frette and Umberto Castagnoli. The first of their articles begins by stating “A new spirit is born”. Italy according to the Gruppo 7 should dictate this new spirit to other nations, a spirit that has a new need for clarity and order, in which there would be no incompatibility between past and present. We must therefore not break with tradition but on the contrary, pursue a continuity in the transformation. Ancient Rome, as the young architects note, produced a few basic building types – the temple, the basilica, the thermal baths etc … In short, Rome “built in series” and this is the basic example that responds to new contemporary needs. To do this, the architect must work in group for a selection of the new types of modernity.

Terragni’s first projects are the implementation of the principles identified by the Group. For example in restructuring of the Metropole-Suisse hotel in Como (1926-27) he chooses to transform tradition by using the same facade elements – vases, candlesticks, pine cones – but transfiguring them into completely new shapes and rhythms. In the Monument to the fallen in Erba Incino (1926-32) and in the Stecchini and Pirovano funeral kiosks (both 1930-31) in Como, history and memory merge together to constitute modern examples. The architecture of the Monument, for example, is modern because it manages to do so that its content, the memory of the fallen, does not break through a shape, a style or decoration but throuhg the real experience of those who walk there, in the light and landscape consuming it.

The project that will bring him notoriety, however, is the Novocomum apartment complex in Como (1927-29) also due to the trick with which Terragni will circumvent the problems of the decoration commission by presenting to the Municipality a disguised project with tympanums and pilasters. The building caused a great uproar especially for the corner solution consisting of a large one glazed ellipse set under a cantilevered right angle. The Novocomum was unanimously considered the first modern building in Italy; Terragni was then 24 years old.

In a few years the events of modern Italian architecture followed one another in a whirlwind and in 1932 the exhibition of the revolution fascist (1932) ensured national fame to Terragni who set up Room O with a large photomontage of hundreds of outstretched hands driven by the giant turbins of revolution.

Between 1932 and 1936 there was a favorable phase for modern architecture in Italy as Fascism was the only totalitarian regime that seemed to be wanting to present itself through a modern language, equally opposed to both Nazism – mind of the immediate closure of the Bauhaus in ’33 – and Stalinist Communism, but also to democratic countries: everywhere the classicism seemed to prevail.

Above all, however, these were the years of the Casa del Fascio in Como (1932-36) for which, underlining his idealism, Terragni will renounce any compensation. Thanks to the decisive help of his brother Attilio, an exponent of the Pnf of Como and later mayor citizen, Giuseppe Terragni designs a compact volume only apparently seeming closed on itself, as Manferdo Tafuri wrongly wrote. Not only is the building open with numerous glass openings, but also all the drawings try to emphasize the relationship of visual permeability, that’s because, as declared by Mussolini, “Fascism is a glass house” and the work going inside it therefore had to be shown without hesitation.

In addition, the orientation of the building following to the grid of the Roman cardo and decumanus of the city of Como showes that the Casa del Fascio is intended to be the first stone of a new city in continuity with the old one.

Giorgio Ciucci wrote “the rationality invoked by Terragni is a rationality of golden proportions, of invisible orders, of relationships that go beyond the physical and that you can only guess “and this is also true for some extraordinary projects not realized like those of Palazzo del Littorio (1934) and especially the Danteum (1938).

1936 is the happiest year for Terragni as he has the opportunity to create the airy and articulated Sant’Elia kindergarten which inaugurates a series of projects – that of the lake villas. However, 1936 is also the year of proclamation

of the Empire and the definitive defeat of modern architecture in Italy, henceforth the primary need for regime would be a style that obeyed criteria of grandeur and monumentality, that was the E42 style.

Hardly anyone will notice the last building built by Terragni, the Giuliani Frigerio house (1939-40) because it is difficult to assimilate to any other contemporary European architecture project. The Giuliani Frigerio, placed a few tens of meters from his first work, the Novocomum, belongs to the last planning season of Terragni when the synthesis of form reaches the apex of interpenetration. From many sketches it is clear how he designed the building directly in section and the result is an incomparable work in its solitary formal complexity.

However, Terragni’s career was abruptly interrupted by the call to arms in 1939, when Giuliani Frigerio was non yet completed, in 1941 he will take part in the disastrous Italian campaign in Russia. He returned to Como psychically mined, emptied: he would apologize for no reason to whoever he met. He died only 39 years old. In the postwar period the political meanings that Terragni himself had wanted to attribute to his work would be removed for a long time: on one side Bruno Zevi judging Terragni’s architecture “intrinsically” anti-fascist because anti-rhetorical, on the other Peter Eisenman who with his syntactic analyzes will tend to completely abstract Terragni from his context, thanks to these although Terragni has experienced a renewed international fame. Historians like Giorgio Ciucci and more recently, Paolo Valerio Mosco have instead returned Giuseppe Terragni to his right historical dimension: that of an architect who wanted to be part of a political movement and at the same time to fight for a congruent architectural movement according to an austere concept of life that Giovanni Gentile, in the Manifesto of intellectuals del Fascism (1925), defined as “religious seriousness”.

A TRIBUTE TO GIUSEPPE TERRAGNI BY FRANCO BIZZOZZERO

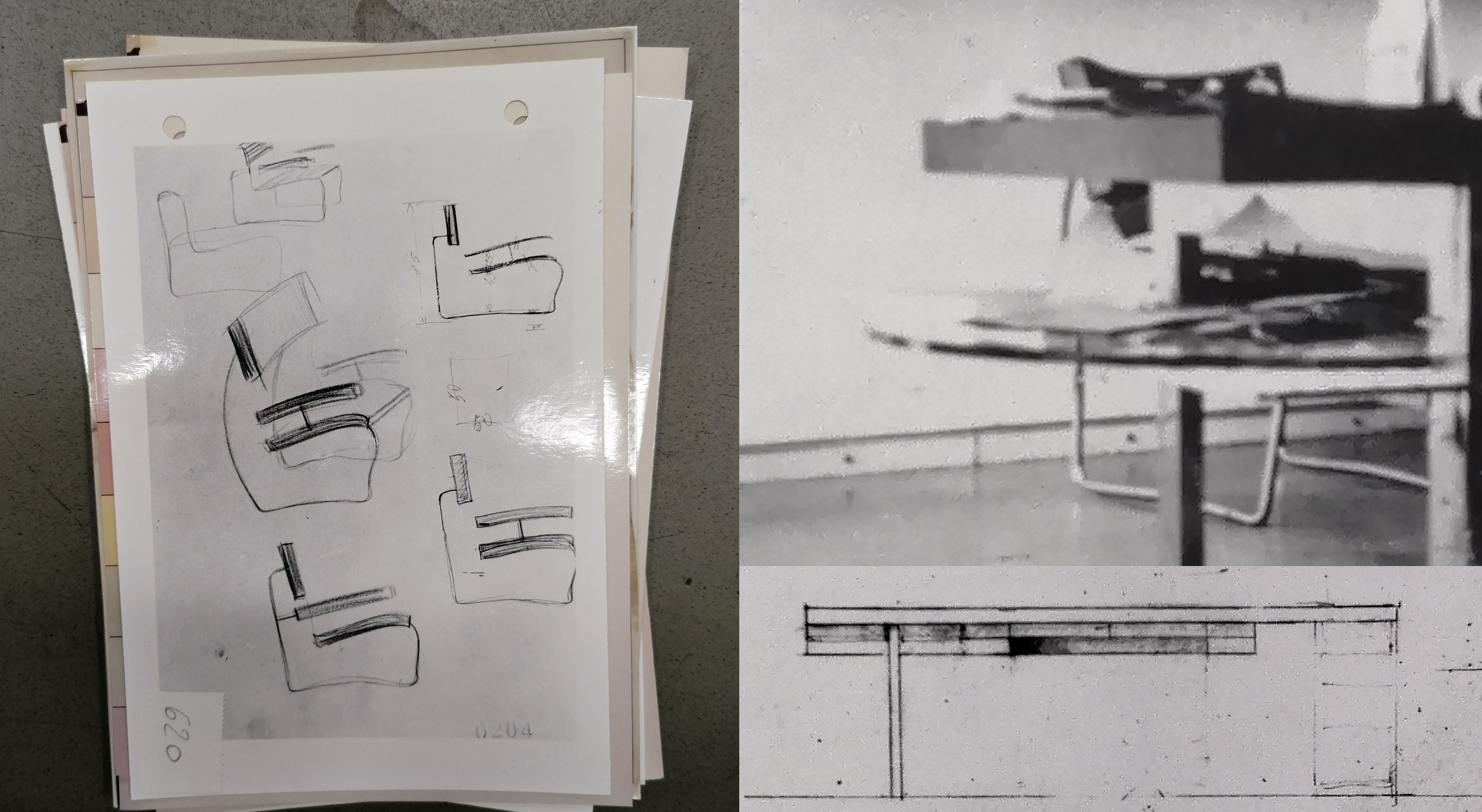

The tribute to Giuseppe Terragni starts from an accurate research that has brought to light some signs here and there in the compendium of studies kept in the Terragni Archive, which either could have been waiting for a later furnishing commitment or just be some piece of quick note, placed on the margins of more complex tables as a reminder for further development.

And this has brought attention among many sketches to a drawing, very ethereal in the sense of conservation, made of completed yet barely mentioned lines, as if there were no need for anything but three-dimensionality to give it life: overlapping each other, a seat in front of furniture, two levels put together in an inseparable enitity.

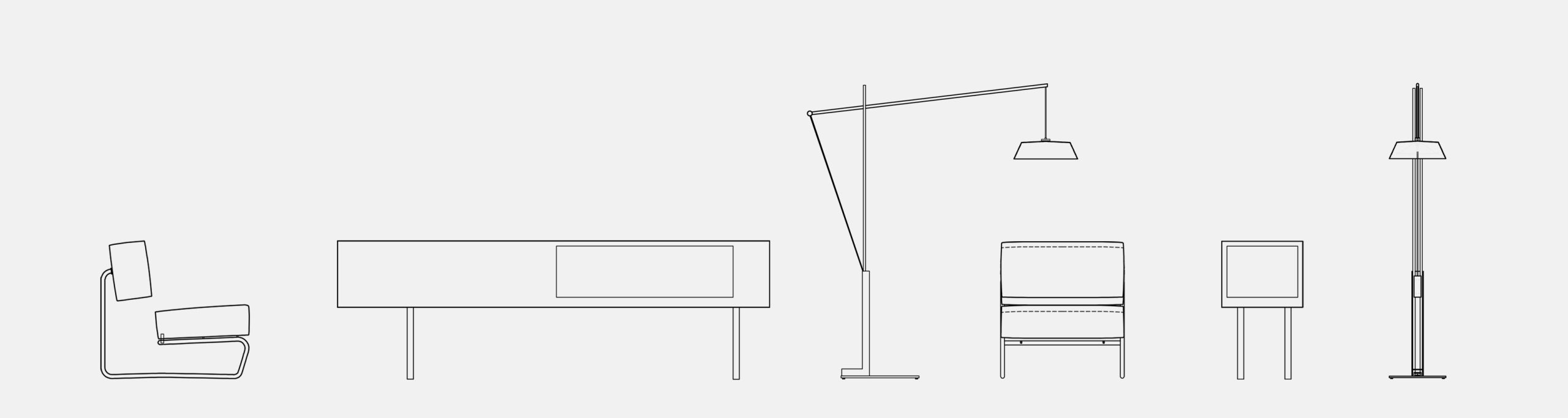

We expect it will be the sense, hopefully successful, of a posthumous tribute to his multifaceted personality, through the creation of three NEW furnishing elements: the countermobile, the armchair and the lamp.

The operation, originating from a deep respect for these assumptions, induces a heartfelt sharing of the rationalist creative process that still remains strong and present almost a century later.

A process that has contributed over the time to the emergence of a new sensitivity in dealing with contemporary issues, involving the professional training of generations of architects and culturally shaping a local productive fabric (Como, Lombardy) that represents the excellence of the know-how characteristic of our entrepreneurial Italy.

We approached the sketches of the Master with respect, although aware that the Terragni’s method has always been pragmatic, operational, in close communication with craftsmen. That is to say, those who must stand the technical challenges literally or even identify alternative operational solutions.

A dialectical exchange sincerely respectful of the roles and anyway pursuing a common purpose: the realization of innovative and experimental elements which, by using the best available technique, make it an instrument of high expressiveness.

Inedited

Inedited products homage to Giuseppe Terragni

-

Sideboard GT.Z

€5,370.00 Add to cart -

Lamp GT.LUX

€3,780.00 Add to cart -

Armchair GT.X

€4,400.00 Add to cart

Scale 1:5

Tribute reproductions to Giuseppe Terragni